At the very heart of Europe—a continent that once prided itself on enshrining humanism, tolerance, and the rights of man—a dangerous paradox is igniting in 2025. The same Europe that heralds itself as a bastion of freedom of conscience is fast becoming a stage for something far darker: a climate of open hostility toward Islam and its followers. Mosques are being desecrated. Sacred texts are going up in smoke on city sidewalks. And Muslims are increasingly becoming targets—not just of street-level hate, but of a systemic, media-fueled culture of fear.

This isn’t a rash of isolated incidents. It’s a sustained, escalating pattern. Each mosque vandalized, each hijabi woman attacked, each Quran set ablaze is part of a deeper story—one about the atmosphere that allows it. It’s the silence of institutions, the weaponization of free speech, and the slow corrosion of civil liberties under the guise of defending them. Europe, it seems, has arrived at a dangerous crossroads: where freedom of expression is used to mask bigotry, and the right to be heard becomes the right to degrade.

If left unchecked, this trend won’t just cost Europe the respect of the Muslim world. It threatens the continent’s moral core. Because real democracy is measured not by how it protects the powerful—but how it stands up for the vulnerable. Right now, Muslims are the litmus test. And Europe is failing.

The Slow Creep of Institutionalized Hate

The year 2024 marked a turning point in how Muslims are treated in two of Europe’s largest democracies—Britain and Germany. What began as verbal slurs and sporadic vandalism has snowballed into a coordinated campaign of intimidation. In countries that often tout their liberal values, the backlash against Muslims has moved from rhetoric to reality—taking the form of physical violence, terror, and official indifference.

United Kingdom: The Statistics Are Screaming

According to data from Tell MAMA, an organization tracking anti-Muslim hate, Britain saw a 73% spike in Islamophobic incidents in 2024 compared to the previous year. More than 4,300 cases were reported—including 672 involving physical violence and roughly 1,200 acts of vandalism targeting mosques, cemeteries, and cultural centers.

What’s even more disturbing is the geographic shift. These incidents are no longer confined to urban centers like London, Manchester, and Birmingham. They’ve crept into quieter corners—Yorkshire, Lancashire, the East Midlands—areas previously considered less volatile.

Muslim women bore the brunt of this violence: 61% of victims were female, most wearing headscarves. Many were attacked in broad daylight—on public transit, on sidewalks, even near their homes. In April alone, 48 stabbings were reported, all tied to religious hatred.

“This is the most dangerous time for Muslims in the UK since our organization was founded,” said Saadia Ahsan, director of Tell MAMA. “We’re no longer talking about fringe acts of hate. We’re talking about a cultivated indifference from the state.”

Germany: A Shadow War on Mosques

While the UK grapples with street-level violence, Germany’s version of Islamophobia looks disturbingly institutional. More than 1,550 hate crimes targeting Muslims were reported in 2024—a 24% increase over the previous year and twice the number logged in 2021.

Fifty-four of those incidents involved attacks on mosques. In Munich, Hamburg, Düsseldorf, and Berlin, houses of worship have been firebombed, broken into, and defiled—sometimes with pig heads and blood smeared across entryways. In one case, surveillance footage in Baden-Württemberg captured a group of men breaking into a mosque at 3 a.m., beating the imam with bats and scrawling “Europe is for Christians” on the walls.

Fifty-three assaults on individual Muslims were documented, 18 involving knives. Eleven of those attacks took place in front of children. On a single night in March, seven Muslim women were assaulted in Berlin for wearing niqabs.

And yet, the justice system barely budges. Over 65% of victims didn’t report the crimes, convinced police wouldn’t take them seriously—and often, they’re right. Out of more than 1,500 cases, just 93 made it to court. Only 29 resulted in convictions.

That’s not just negligence—it’s a justice gap that echoes colonial patterns, where whole populations were treated as second-class by design.

This isn’t random street violence. It’s a byproduct of deliberate public messaging. In 2024, more than 28% of headlines in Britain’s most-read tabloids referenced Islam negatively—often linking it to terrorism, “parallel societies,” or threats to “European values.”

In Germany, the Amadeu Antonio Foundation found that one in three parliamentary mentions of Muslims included terms like “radicalization,” “extremism,” or “danger.” And these weren’t fringe politicians—they came from the Bundestag’s major parties.

Even intelligence services are complicit. While pledging to fight extremism, they simultaneously profile Islamic groups—putting 86 under surveillance in 2024. Only four were accused of promoting violence. The rest? Charities, schools, and cultural organizations.

This is no temporary surge. It’s a structural pivot. Violence against Muslims is being normalized. And state indifference is becoming a feature, not a bug, of modern European governance.

Surveys reinforce the trend. In the UK, 38% of respondents see Islam as a “threat to British identity.” Forty-five percent support banning religious clothing in public institutions. In Germany, the picture is even bleaker—52% believe Islam is “incompatible with Western culture.”

These numbers aren’t just data points. They’re the pulse of a rising authoritarianism—camouflaged as secularism and civility.

In 2024, Britain and Germany became laboratories of political hate. As hijabi women are attacked in plain sight and mosques erupt in flames, lawmakers squabble over where “free speech” ends. But those lines were crossed long ago—crossed in the bodies beaten on sidewalks, in the charred pages of Qurans, and in the deafening silence from those in power.

Today’s Europe isn’t the land of religious freedom it claims to be. For Muslims, public faith is becoming a liability. Practicing Islam in public can feel like a sentence. And if this trend continues, tomorrow’s battle won’t be about free speech. It’ll be about survival.

The Sacred Flame of Hate: The Scandal That Redefined Sweden

In 2023, Sweden—long held up as a beacon of neutrality, humanitarianism, and tolerance—found itself thrust into a firestorm that scorched its global image and exposed a nation at war with its own ideals. At the center of this firestorm was a man whose name has since become synonymous with Europe’s crisis of pluralism: Salwan Momika.

On June 28, 2023, during the Muslim holiday of Eid al-Adha, Momika—an Iraqi refugee granted asylum in Sweden—set fire to pages of the Quran outside Stockholm’s central mosque. He did it in full view of the press, with police protection, under the umbrella of free speech rights guaranteed by Swedish law. The backlash was instant and explosive, reverberating across the Muslim world.

Within 24 hours, Pakistan’s parliament issued a unanimous condemnation. Tens of thousands marched in Lahore and Karachi. In Baghdad, protesters stormed the Swedish embassy. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan called the act “a crime against humanity” and froze talks on Sweden’s NATO accession. Iran suspended bilateral cultural programs. Demonstrators filled the streets outside Swedish embassies in Jakarta and beyond.

The Organization of Islamic Cooperation convened an emergency session. Diplomats from Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Algeria, Malaysia, and Kuwait demanded an apology. Several countries—including Iraq, Iran, and Kuwait—recalled their Swedish ambassadors. Under intense pressure, Sweden’s Foreign Minister Margot Wallström issued a statement distancing the government from Momika’s actions but insisted it could not override police decisions on demonstrations, citing constitutional protections.

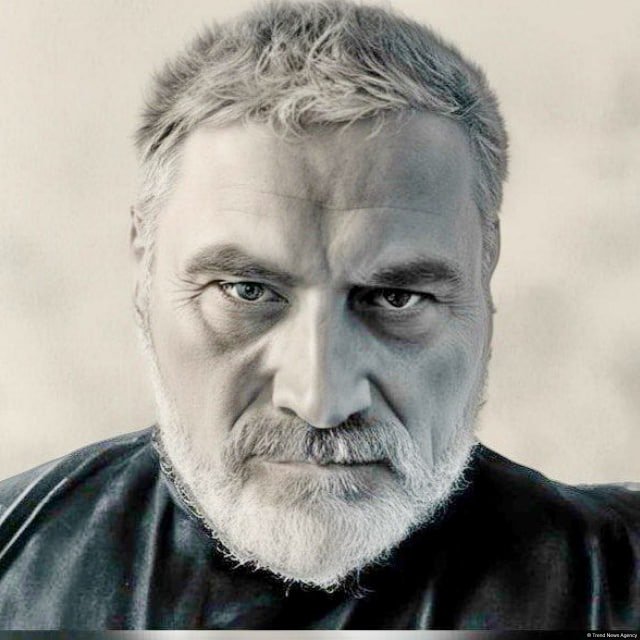

The Man Behind the Fire

Salwan Momika was not an accidental figure. A Christian refugee who fled Iraq in 2018 claiming persecution by Shiite militias, he was granted asylum in Sweden in 2021 and quickly emerged as a provocateur on the far-right fringe. For years, he staged anti-Islam protests, published incendiary content, and issued statements laced with contempt for the Muslim faith.

Complaints flooded in—from Muslim groups and human rights organizations alike—but prosecutors repeatedly declined to act. Sweden’s constitutional framework, bolstered by the 1766 Freedom of the Press Act, grants sweeping latitude to critique religion. That legal shield, while designed to safeguard open discourse, allowed Momika to push the boundaries of hate.

In effect, he became a test case—an unwitting experiment in just how far Sweden’s tolerance could stretch before snapping. When he burned the Quran again in September and December 2023, global condemnation only intensified. To much of the world, his actions weren’t expressions of opinion—they were deliberate provocations, designed to sow division and incite hatred.

The Breaking Point

On January 15, 2025, in a suburb of Uppsala, Salwan Momika was gunned down. The killing, police later confirmed, was premeditated. The suspect—a Swedish citizen of Iraqi descent with ties to a religious group active in the diaspora—had no prior criminal record.

The murder detonated a new round of national soul-searching. Who was to blame? A society that allowed sacred texts to be desecrated with impunity? Or an ideology that responded to provocation with bullets?

Sweden’s political spectrum split down the middle. Left-leaning parties and human rights advocates blamed the state for losing control. The right, meanwhile, framed Momika’s death as an attack on freedom of speech—and used it to call for stricter immigration laws. The Ministry of Justice responded by forming a task force to review legal protections for religiously charged public demonstrations.

Diplomatically, Sweden entered choppy waters. Middle Eastern nations that had been warming to reconciliation now demanded not just apologies, but legislative reform. At the World Islamic Forum in Jeddah, Sweden was formally denounced as a country “that fails to protect its religious minorities.” In response, Saudi Arabia and Qatar canceled business contracts with Swedish firms worth over €2 billion.

Even Sweden’s NATO bid came under renewed scrutiny. Turkey, holding veto power, demanded legally binding assurances that such provocations would no longer be permitted. The alliance’s secretary general issued a rare rebuke, warning that incidents like the Quran burning “undermine the shared values of the bloc.”

A Mirror Held to the Nation

The saga of the Quran burning and Momika’s assassination has become far more than a diplomatic debacle. It is a diagnosis—a searing indictment of Sweden’s struggle to reconcile its liberal ideals with the realities of an increasingly diverse society.

The nation that once welcomed refugees with open arms is now grappling with record-low trust in government—just 31% approval. Among Sweden’s Muslim population, 47% report feeling legally unprotected. Over half—52%—believe Sweden has become openly hostile to Islam.

Momika’s story will be remembered not as a parable of free speech, but as a tragedy of national self-deception. A tragedy in which the charred remains of the Quran became a mirror—reflecting not just one man’s hate, but a society’s failure to confront it.

Europe’s Invisible Wall: How Muslims Are Being Denied Equal Rights

When European leaders speak of human rights, equality, and inclusion, the rhetoric is lofty—aspirational, even. But for millions of Muslims across the continent, these words often ring hollow. Behind the polished language of democracy and tolerance lies a harsher reality: one of systemic discrimination that touches nearly every aspect of daily life—from job applications and housing searches to classrooms and government offices. And the numbers tell the story better than any press release ever could.

In a wide-reaching study across 13 EU countries—including Austria, Germany, Finland, France, and the Netherlands—more than 35% of Muslim respondents reported facing discrimination in the job market. In Austria and Germany, that figure spikes to nearly 70%. One in four rejection letters went to applicants with “non-European” names—even when their qualifications matched those of their native-born peers.

The discrimination hits especially hard for Muslim women who wear the hijab. About 45% of Muslim women under the age of 30 reported being denied jobs explicitly because of their headscarf. Employers didn’t bother hiding their bias: "You wouldn’t fit in with the team." "It’s not the right image for our clients." "We have a strict dress code."

Young Muslims in the EU are disproportionately targeted by overlapping forms of exclusion. According to recent studies, over 58% of young Muslim women—born and raised as EU citizens—reported facing discrimination in schools and universities. They’re penalized for wearing religious attire, barred from extracurriculars, denied access to gym classes unless they remove their hijab. Many are suspended or expelled under vague “school dress code” violations.

The consequences are stark. The early dropout rate among Muslim students is nearly three times the EU average—around 30% compared to 10%.

Housing discrimination is another glaring issue. In cities where rental demand is high, up to 40% of Muslims report being turned away by landlords. Legal protections exist on paper, but in practice, phrases like “Europeans only,” “no children,” or “no veiled women” are all too common—especially in France, Belgium, and the Netherlands.

As a result, Muslim families are often pushed into segregated neighborhoods with substandard housing and limited access to healthcare, education, and public services. This deepens cycles of poverty and isolation—and makes upward mobility a near impossibility.

In some parts of Europe, being visibly Muslim is not just a social liability—it’s a political target. France offers a textbook example. In 2004, it passed a law banning “conspicuous religious symbols” in public schools—a measure that disproportionately affected Muslim girls. In 2021, lawmakers debated banning the hijab in all public spaces for minors.

Belgium, Switzerland, and parts of Germany have passed or floated bans on burkinis, burqas, and niqabs—even though their use is rare. The issue, politicians argue, isn’t practical but symbolic. The hijab, in their framing, is no longer a matter of personal identity—it’s a perceived threat to secular order.

And then there’s the media and political discourse, which has become increasingly hostile in recent years. Across the EU’s largest countries, anti-immigrant rhetoric has gone mainstream. Politicians chasing easy popularity have weaponized public fear with buzzwords like “Islamization of Europe,” “threat to traditional values,” and “Muslim disloyalty.”

In one German survey, 42% of respondents admitted they felt “uncomfortable” living next to Muslims. In Austria, 61% believe Islam is “incompatible with European life.” These attitudes didn’t arise in a vacuum—they’re the product of decades of media narratives that consistently cast Muslims as terrorists, threats, or problems to be managed.

Behind Europe’s polished self-image lies an invisible wall—one that quietly but powerfully excludes millions of its Muslim citizens from the very ideals it claims to uphold. And unless that wall comes down, the continent’s vision of democracy will remain, for many, nothing more than a slogan.

Europe’s Tightrope: Navigating the Line Between Faith and Free Speech

In July 2023, when an Iraqi refugee set fire to the Quran in front of a mosque in central Copenhagen, Denmark was thrust into the eye of a geopolitical storm. Outrage rippled not only through the Muslim world—where embassies were attacked and Danish goods boycotted—but across Europe itself, where the centuries-old tension between freedom of expression and religious tolerance reached a boiling point.

Two months later, Denmark’s government took an extraordinary step: it introduced—and swiftly passed—a law criminalizing “improper treatment” of sacred religious texts, explicitly including the Quran, the Torah, and the Bible. Legally, that meant bans on burning, tearing, defacing, or publicly desecrating these scriptures. Offenders now face fines of up to €10,000 and, in some cases, criminal prosecution.

The move landed like a thunderclap—both domestically and abroad.

Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen’s government framed the law as a pragmatic safeguard. The goal, officials explained, was to ensure “public order,” protect “international interests,” and avoid a repeat of the summer’s diplomatic meltdowns. By August 2023, 15 Muslim-majority nations had pulled their ambassadors from Copenhagen. Saudi Arabia froze investment guarantees worth an estimated $300 million.

But to see the law solely as a foreign policy maneuver would miss the deeper shift it represents. Denmark—long known for its fierce secularism and staunch defense of free speech—was also the site of the infamous 2005 Jyllands-Posten cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad, and the 2015 terror attack on a cultural center hosting a freedom-of-expression event. Against that backdrop, the 2023 law marked a symbolic turning point: a public admission that absolute free speech might, at times, undermine social peace.

Public reaction in Denmark was mixed. A poll conducted in October 2023 found that 54% of Danes supported the ban on desecrating religious texts, with support among young adults (ages 18–29) reaching 63%. For many, the law reflected a growing fatigue with conflict and a shift in generational values.

Still, backlash came swiftly. Opposition parties, including the Liberal Alliance, and major human rights groups blasted the law as “a concession to Islamist pressure” and “a dangerous precedent.” Their fear: that once you begin regulating speech to protect sacred symbols, you're on a slippery slope toward suppressing criticism, satire, and artistic expression.

By December, Danish writers and artists published an open letter comparing the measure to a “secular blasphemy law”—a chilling phrase in a country that had long prided itself on intellectual freedom.

Legally, the law broke new ground in Scandinavia. It challenged the contours of Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which protects free speech but allows states to impose limits “for the prevention of disorder or the protection of others’ rights.” The European Court of Human Rights has, in the past, upheld such restrictions—but usually in cases involving incitement to hatred, not mere “disrespect” toward religious texts.

And that’s precisely what alarms free speech advocates: the Danish law doesn’t just punish hate—it codifies reverence. It protects not individuals from harm, but symbols from offense.

In January 2024, the European Commission opened a review of whether the law aligns with EU legal standards. While a full reversal is unlikely, the symbolic shockwaves are already spreading. In the Netherlands, Austria, and even France, lawmakers are floating similar proposals, emboldened by recent mosque attacks and anti-Islam provocations.

Denmark’s decision reflects a broader European reckoning—one where the old liberal compact is being recalibrated. Can a secular democracy draw limits around speech without betraying its founding values? Can it protect social cohesion without privileging particular beliefs?

The debate is far from over. But one thing is clear: Europe is no longer just navigating questions of law—it’s negotiating the soul of its identity.

Europe at the Mirror: The Danish Law and the Cracks in the Continent’s Moral Compass

Denmark’s recent legislation banning the desecration of religious texts isn’t just a legal adjustment to soothe a diplomatic crisis. It’s a symptom—of a deeper, unresolved fracture running through the heart of Europe. A fracture born of the continent’s inability to reconcile two of its most cherished principles: freedom of expression and the protection of religious belief. One defends the right to mock; the other demands the right to revere. And today, Europe is losing its grip on both.

Right now, the law shields the Quran. But tomorrow, it could be used to silence criticism of the Church—or, just as easily, to punish satire targeting Islam. What seems like a short-term fix to international outrage risks becoming a long-term precedent for censorship cloaked in sensitivity. The line between safeguarding dignity and policing thought has never been thinner.

This is not a localized skirmish in the Danish parliament—it’s a cultural fault line that cuts across Europe’s newsrooms, courtrooms, and classrooms. It forces a question that the continent has avoided for far too long: What does it truly mean to defend universal rights? And what happens when those rights collide?

The Danish law is, at best, a gesture of crisis management. At worst, it opens the door to a dangerous inversion—where human rights are no longer about protecting people, but about shielding ideas from offense. That shift creates fertile ground for manipulation, suppression of dissent, and the slow, quiet erosion of democratic integrity.

Europe now stands at a crossroads. It can either reaffirm its commitment to foundational freedoms—or succumb to the fear of popular backlash, whether domestic or global. What’s at stake isn’t just free speech. It’s Europe’s very identity as a place where reason and dignity are meant to prevail over outrage and orthodoxy.

A Mirror Held to the Continent

What does Europe see when it looks in the mirror? Not the reflection of progress, but the spreading cracks of a continent in denial. Not the glow of democratic ideals, but the shadow of a civilization drifting into moral amnesia.

Today’s Europe may present itself as a showcase of rights and liberal values—but for millions of Muslims, it feels more like a maze of suspicion, coded discrimination, and invisible rejection. Not a home of equality, but a daily struggle against the quiet contempt of institutions that speak the language of rights but act with averted eyes.

The illusion of inclusion shatters under the weight of lived experience—where a hijab is treated as a provocation, a mosque as a target, and “integration” is often shorthand for erasure. Where governments respond to systemic bias with ritual incantations: “We condemn all forms of extremism.” Empty phrases that do little when Qurans are burning and courts are silent.

Europe is inching toward a precipice. Either it becomes a continent where faith is not a verdict and freedom is not a luxury—or it settles into a status quo where equality ends at the edge of a house of worship.

This is not a battle over tolerance—it’s a test of humanity. And as long as laws are written to protect symbols instead of people, as long as silence is mistaken for neutrality instead of complicity, Europe isn’t just losing credibility—it’s losing itself.

And if it fails to course-correct, the next time it peers into that mirror, it may not recognize the face staring back.