Türkiye has entered a new phase in its long battle for control over the state—not against armed insurgents or opposition parties, but against a covert, deeply embedded religious network that has operated for decades behind a mask of piety. On the morning of May 15, 2025, the country woke up to headlines announcing sweeping arrests and raids. The target: the Süleymancı community—a religious order that has, until now, largely operated in the shadows, but whose reach, discipline, and political sophistication have long invited comparison to the once-powerful, now-outlawed FETÖ network.

The arrest of four key figures, including a senior member of the judiciary, wasn’t just a legal maneuver—it was a thunderous strike at the heart of a clandestine structure accused of running a parallel state apparatus under the guise of religious education and charity work.

The night before the crackdown, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan delivered a speech before lawmakers from his ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP). Without naming names, he issued what many saw as an unmistakable ultimatum. He condemned a "dark organization" allegedly tied to foreign intelligence, embedded in Türkiye's courts, business world, religious institutions, and bureaucracy. The message was razor-sharp and unmistakably targeted.

Nobody in Türkiye needed a decoder ring to figure it out. Analysts, journalists, and insiders immediately knew who Erdoğan meant: the Süleymancı movement. One of the country’s most insular and disciplined religious communities had just lost its political immunity. The president’s rhetoric was soon followed by forceful action. The operation marked not just a law enforcement campaign—but a major inflection point in Türkiye's campaign to reclaim sovereignty over its own institutional backbone.

Who Are the Süleymancıs?

The Süleymancı community is more than a conservative Sufi order. It’s a sprawling, transnational network with its own schools, dormitories, charities, and ideological playbook—a quasi-state embedded within the Turkish Republic and among its global diaspora. With roots stretching back to the 1920s, it has evolved from a pious brotherhood into a powerful sociopolitical force, influencing everything from education policy to bureaucratic appointments and even Türkiye's foreign policy rhetoric.

At the center of this movement stands Süleyman Hilmi Tunahan, a revered Islamic scholar and graduate of Istanbul’s Fatih madrasah. Following Atatürk’s secularist reforms and the banning of traditional Islamic schools, Tunahan began secretly teaching the Quran, laying the foundation for a community defined by secrecy, hierarchy, and resilience.

The 1950s brought liberalization under Prime Minister Adnan Menderes, giving the Süleymancı movement space to go public with parts of its operations. Their real growth, however, came after the 1980 military coup, when the regime quietly encouraged religious organizations to balance the secular elite. It was during this era that the Süleymancıs morphed into a state within a state, building parallel structures of authority and influence.

According to Türkiye's Ministry of National Education and the Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet), by 2024, the Süleymancı network operated at least 300 affiliated educational institutions. These include Quran courses, dormitories for teenage boys known as “yurtlar,” and vakıfs—private religious foundations controlling the network’s financial infrastructure.

In Istanbul alone, there are some 80 such institutions, known for their strict internal discipline, emphasis on Arabic-language theology, and self-contained culture. Prosecutorial investigations between 2020 and 2023 uncovered disturbing allegations of physical punishment, ideological indoctrination, and the deliberate isolation of youth from the outside world.

Erdoğan’s Message: No More Parallel States

The symbolism of Erdoğan’s crackdown cannot be overstated. Türkiye has been down this road before—with FETÖ, the Gülenist network accused of orchestrating the failed 2016 coup. The trauma of that event still hangs heavy over Turkish politics. The president has since pledged never to allow another covert power structure to operate under his watch.

By targeting the Süleymancıs, Erdoğan is making it clear: loyalty to the state cannot be conditional, negotiable, or quietly outsourced to cloistered religious hierarchies. The war is no longer just about ideology—it’s about control, legitimacy, and the state’s monopoly over influence. In today’s Türkiye, that’s a fight to the finish.

The Shadow Beyond the Border

The Süleymancı movement isn’t just a domestic phenomenon. Over the years, it has quietly extended its reach far beyond Türkiye's borders, evolving into a global web of affiliated organizations. According to a report by Türkiye's National Intelligence Organization (MIT) and findings from a parliamentary committee on destructive sects, the group operates more than 100 foreign outposts under various names—from educational foundations to cultural associations.

Germany has become a particular stronghold. The country’s Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (BfV) has identified at least 36 community centers tied to the movement, with ties to religious schools, student dormitories, and madrasas in Berlin, Cologne, Munich, and Hamburg. In the U.K. and Austria, the Süleymancı have collaborated with Muslim associations under the banner of integration programs, but insiders say the real purpose was to build insular enclaves—spaces where young people were groomed to embrace ideological loyalty to the Turkish state and spiritual leaders in Istanbul.

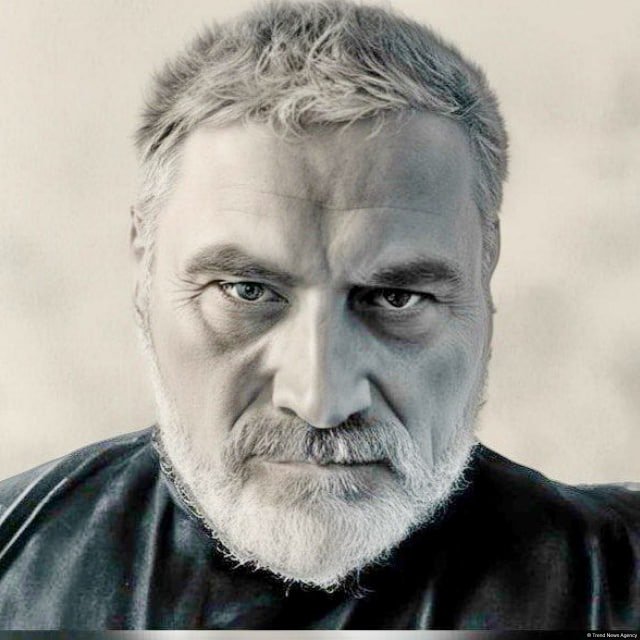

At its core, the movement preaches a deeply conservative brand of Islamic traditionalism, fused with rigid institutional discipline. Süleyman Hilmi Tunahan, the movement’s founder, is revered within the community as a reformer of the faith, and today’s leadership claims direct spiritual lineage. The current top figure, Alihan Kuriş, is a charismatic operator seen as the brain behind the network’s personnel strategy and financial coordination, managing operations through a close circle of trusted lieutenants.

One of the more telling features of the group is its lifelong loyalty model. Youths who pass through the Süleymancı dormitory system—known as yurtlar—are expected to maintain ties with the organization for life. This quasi-oath ensures a pipeline of ideologically aligned individuals, embedded across state and private sectors, without the need for formal membership rolls. It’s a playbook strikingly similar to the one used by Fethullah Gülen to build the FETÖ network, albeit with a more subdued and conservative tone.

The movement’s administrative structure is built around regional coordinators and supervisors funded by central foundations. Most financial operations run through registered charities, framed as educational or cultural efforts. According to internal documents from Türkiye's Ministry of Interior, in 2023 alone, the movement’s related foundations reported a combined turnover of roughly 1.4 billion Turkish lira—around $70 million at the time.

Unlike the Gülenists, the Süleymancıs have never sought visibility. Their influence in the state apparatus was subtle, deliberate, and often went undetected—until now. Over the years, they quietly infiltrated sensitive institutions: the Ministry of Interior, the judiciary, the tax authority, the education system, even the diplomatic corps. According to İbrahim Usta, former head of HR at the Ministry of Justice, dozens of prosecutors and judges in the early 2020s were found to have trained in Süleymancı dorms. These ties were rarely documented but widely acknowledged in unofficial circles.

Former AKP lawmaker Fatih Süleyman Denizolgun says he tried to raise the alarm as early as 2018, warning about the group’s growing presence in critical nodes of power. At the time, the ruling party opted to avoid confrontation with such an entrenched network. But after the fall of Gülen in 2016, President Erdoğan began a slow, calculated purge of other religious structures deemed capable of building “states within the state.”

So when the crackdown came in May 2025, insiders weren’t surprised. After Erdoğan effectively painted a target on the group in his May 14 address, the follow-up was swift and precise. Authorities detained not just religious figures, but individuals linked to the judiciary, finance sector, business elite, and political circles. The strategy mirrored the FETÖ takedown: isolate the operatives, freeze the funding, discredit the brand, and bring down the structure through legal and media pressure.

On the same day, NGOs in several European capitals issued public statements accusing Ankara of “religious cleansing.” But for Turkish authorities, this is not about faith—it’s about sovereignty. It’s about reasserting control over subterranean networks that have quietly sculpted power structures from behind the scenes for decades.

In that light, the Süleymancı case is just the latest chapter in Turkey’s broader fight to dismantle the “deep state” and re-center power within the official institutions of the republic. The only question that remains: how many more of these silent networks lie dormant within the Turkish bureaucracy—and does the regime have the resolve to finish the job?

The Hidden Elite

The history of religious-political brotherhoods in Türkiye is a history written in shadows. Behind the façade of official secularism lies a deeper, more elusive story—one of quiet networks wielding enormous, often unseen influence. Among these subterranean forces, none have proven as resilient or as quietly pervasive as the Süleymancı movement. Over the decades, this insular religious order has built not just a parallel system of education and spiritual instruction—but a stealth apparatus that has burrowed into the core of the Turkish state.

A 2019 report from Turkey’s Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet) paints a striking portrait of the movement. Described as rigidly hierarchical and closed to outsiders, the Süleymancıs outwardly profess loyalty to official Islam, but maintain their own doctrinal quirks that border on sectarianism. The report—widely circulated in academic and bureaucratic circles—highlights their embrace of the so-called “Noah’s Ark” ideology, a belief that only members of their community are among the spiritually “saved.” One tangible expression of this is their refusal to pray behind imams who do not belong to their order—a stance that runs counter to the dominant Hanafi school in Turkey and underscores their theological separatism.

This strain of religious isolationism hasn’t gone unnoticed. Since the early 2000s, reports from Türkiye's state institutions, including the pro-government think tank SETA and the Presidential Academy of Public Administration, have flagged the Süleymancıs as a force operating behind the scenes—nominally apolitical, but with clear influence over the bureaucracy, local governments, and even the national legislature.

The movement’s political footprint began to emerge in the late 1980s, first via minor parties, and then more aggressively through mainstream political vehicles. Analyses of the 1991, 1995, and 1999 parliamentary elections reveal Süleymancı-linked candidates embedded within the ranks of the Welfare Party (Refah Partisi), the Motherland Party (Anavatan Partisi), the Justice Party (Adalet Partisi), and even the secularist Republican People’s Party (CHP). As Professor Necmeddin Kaya of Bilkent University put it, “The Süleymancıs weren’t playing to control the system—they were playing to infiltrate it.”

That long game paid off during the AKP era. As President Erdoğan waged war on the military elite and secular judiciary, religious orders like the Süleymancıs gained unprecedented access to state power. But as former AKP lawmaker Mehmet Metiner admitted in a 2023 interview on A Haber, “While we were focused on taking down Gülen, we failed to see that other, more discreet religious networks had moved in to fill the vacuum.”

Nowhere was that shift more evident than within the Ministry of Interior. Furkan Sezer, a former Istanbul police official who fled to the Netherlands in 2021, provided explosive testimony to a Turkish parliamentary inquiry the following year. In an 88-page report, Sezer alleged that by 2020, as much as 20 percent of senior police leadership had ties to the Süleymancı network. He described a structured, quasi-corporate system of career advancement based not on merit, but on allegiance to the brotherhood.

Sezer’s claims were partially corroborated by an internal audit from the Ministry of Interior’s inspector general in 2021. In provinces like Kocaeli, Kayseri, and Antalya, officials discovered graduates of Süleymancı-funded Quran courses occupying high-level posts—bypassing competitive hiring processes entirely. Leaked emails and internal memos revealed the existence of “unofficial candidate lists” approved outside of the state’s formal personnel apparatus.

The revelations prompted closed-door hearings in parliament. While much of the content remains classified, opposition newspaper BirGün later published excerpts of internal memos documenting direct pressure on hiring committees and religious-themed corporate events allegedly used to coordinate appointments.

But the most alarming nexus may be the judiciary. A 2024 investigation by the media consortium Medya Atlası identified at least 47 judges and prosecutors appointed between 2017 and 2023 who had trained in Süleymancı-run institutions. One piece, titled Tasnifli Adalet (“Classified Justice”), revealed that high-profile court rulings had been shaped by actors reportedly in close contact with Alihan Kuriş—the current head of the order.

Kuriş himself, the grandson of a close disciple of founder Süleyman Tunahan, is increasingly viewed as a power player in his own right. Between 2020 and 2024, he made multiple appearances at closed-door business forums co-hosted with Türkiye's export-import associations—suggesting that the movement’s reach now extends beyond religion and government into the world of big capital. Former MP Fatih Süleyman Denizolgun was blunt in his assessment: “My brother Alihan wasn’t building a religious community. He was building a new vertical of power—one that answers to neither Diyanet nor the government. He knew Gülen’s time was up, and he wanted that throne.”

Taken together, the evidence paints a chilling picture. The Süleymancıs are not merely a brotherhood or a network of Quran schools. They are a high-functioning, semi-clandestine loyalty machine—embedded deep inside Türkiye's state structures. They have no interest in public office. They’ve learned to rule from the backseat. And that, perhaps, is what makes them more dangerous than any party, any imam, or any overt political actor.

No More Shadows

From Ankara’s perspective, what’s unfolding isn’t just a power play—it’s a matter of national survival. In an era defined by volatile global realignments, Türkiye is working to consolidate its chain of command. Parallel centers of influence, especially those outside the framework of state control, are no longer seen as merely troublesome. They’re systemic vulnerabilities.

This is especially critical as Türkiye strengthens its presence in sensitive domains like defense, cybersecurity, energy, and geoeconomics. The infiltration of ideologically autonomous actors into these fields isn’t just a bureaucratic glitch—it’s a potential conduit for foreign influence, data leaks, and strategic sabotage.

The reaction from the Süleymancı network was telling. In the days following President Erdoğan’s warning shot and the first wave of arrests, panic rippled through the system. Foundations and companies tied to the community scrambled to dissolve subsidiaries, transfer assets, and shutter local branches. According to Türkiye's Commercial Registry Directorate, at least 24 foundations and 17 businesses linked to Kuriş and his inner circle were either shut down or restructured within 72 hours. The message was clear: this wasn’t a temporary crackdown—it was a systematic dismantling.

The End of Parallel States

The Erdoğan government isn’t just issuing ultimatums—it’s drawing a historical line in the sand. Türkiye is signaling the close of an era: there will be no more power-sharing with informal authorities. The president’s intervention is not a show of brute force—it’s an act of state self-preservation.

This isn’t a war on faith. It’s a defense of sovereignty—one redefined in the 21st century not just by borders, but by the monopoly on decision-making. When unregulated power structures begin to control recruitment pipelines, influence strategic assets, and insulate themselves from accountability, they cease to be benign spiritual communities. They become alternative states.

And so, the crackdown on the Süleymancıs is more than a law enforcement operation—it’s a historic turning point. Türkiye is facing its institutional reckoning. A nation that survived a violent coup attempt, weathered regional upheaval, and beat back wave after wave of domestic subversion is now taking on its most entrenched internal threat: the invisible networks that have metastasized within its governance structure.

This is not about theology. This is not about spiritual jealousy. This is a purge designed to reclaim the Republic’s exclusive right to define who wields influence—and how.

The Prologue, Not the Epilogue

The arrests are not the end of the story. They are just the opening chapter. What comes next is the real battle: the forensic dismantling of off-shore financial webs, the purge of bureaucracies infiltrated by ideologically loyal operatives, and, critically, a national reckoning over the role of religious networks in the life of a modern secular republic.

The signal from the top could not be clearer: Türkiye will no longer share authority with orders, sects, or foundations that multiply loyalties faster than they submit to law. This is not about repression—it’s about returning to first principles: that a state is not a patchwork of side deals, but a sovereign structure endowed with will, tools, and the right to govern.

Now comes not just the purge, but the reset. In a climate of mounting geopolitical pressure, economic targeting, and soft power offensives through culture, human rights, and diaspora politics, Türkiye is choosing the hard path of sovereign reconstruction. It’s a path full of friction, but one Ankara sees as essential to the survival of the Republic.

The Süleymancı network is just one face of the parallel state. Tomorrow, another brotherhood, another foundation, another ideological syndicate may find itself under scrutiny. That’s no longer surprising—because Türkiye is no longer a laboratory for ideological experiments. It is a sovereign actor, reasserting control over its destiny. And in the new rules of this game, there’s no longer room for players who won’t play by the state’s rules.